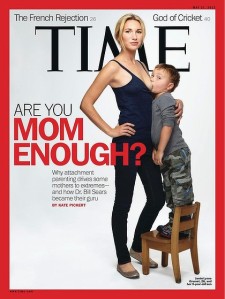

Last week I wrote a piece for ‘The Conversation’ discussion website (http://theconversation.edu.au) about the US edition of Time magazine, 21 May 2012, that featured a cover image of young, attractive woman breastfeeding her three-year-old son (http://theconversation.edu.au/time-2-extreme-parenting-time-magazine-style-7055). I looked at the various responses to this cover image on the internet. Many of these were from mothers themselves or from professional female commentators and bloggers.

What I found was interesting. Some people were horrified at the idea that a boy who could be old enough to remember suckling from his mother’s breast will still be doing so. There were many claims that he would be humiliated when he grew older at being featured in such a controversial and public image. The notion that a child as old as three was still breastfeeding seemed abhorrent to some. Breastfeeding here becomes sexualised and bestowed with incestuous meanings, simply because the child is old enough ‘to remember’ gaining comfort and pleasure from his mother’s breast. The fact that his mother was slim, attractive, young, dressed in a hip manner in tight black jeans, and blonde, simply added to the sexualisation of the image.

Other commentators were relatively accepting of the breastfeeding, but took offence at the headline of the cover, which read ‘Are you Mom enough?’. These are fighting words, suggesting that women who do not engage in practices such as breastfeeding for years are not ‘good enough’ mothers. The words ‘Mom enough’ imply that there are gradations of ‘Momness’ (to use a rather clumsy neologism) and that ‘real Moms’ are those who engage in ‘extreme parenting’ . ‘Extreme parenting’ was a term also used on the front cover and in the detailed article published within about attachment parenting and one of its most prominent advocates, American paediatrician Dr Bill Sears.

In contrast to the deliberate provocation of the cover imagery and wording, I found the article quite well-balanced, looking at both the pros and cons of engaging in attachment parenting, which involves baby-wearing in slings and co-sleeping as well as extended breastfeeding and breastfeeding on demand. Sears argues that these practices, based on age-old customs still found in non-western societies, contribute to infants’ physical and psychological wellbeing. According to the article, more and more mothers are taking up his advice and engaging in attachment parenting practices.

Nonetheless, as case studies used in the article attest, attachment parenting (also ‘extreme parenting’ according to Time) can be extremely hard work for the mothers who adopt it. In fact, it clashes with the contemporary notion that both women and men are autonomous individuals, freely making choices about their lives and engaging actively in the workforce without constraint. Attachment parenting directly challenges these assumptions, because it counters the notion of the mother and the infant or child as autonomous subjects. Instead, it rests upon the assumption that the mother-child dyad is interembodied, that the boundaries between the two are blurred rather than distinct, and that the mother, instead of actively seeking to foster autonomy and independence in her child, will follow its cues and submit to its neediness for her bodily presence.

For people in contemporary western societies, these are highly challenging and confronting concepts. This perhaps explains the controversy over the cover image and the use of the term ‘extreme’ to describe attachment parenting.

For sociological studies on women’s experiences of attachment parenting, see the work of Charlotte Faircloth: http://kent.academia.edu/CharlotteFaircloth. For my own work on concepts of infants’ bodies, see Deborah Lupton (in press) ‘Infant embodiment and interembodiment: a review of sociocultural perspectives’, Childhood and Deborah Lupton (2012) Configuring Maternal, Preborn and Infant Embodiment. Sydney Health & Society Working Paper No. 2. Sydney: Sydney Health & Society Group, available at http://hdl.handle.net/2123/8363.