This is an excerpt from chapter 3 (on digitised embodiment) in my forthcoming book Digital Health: Critical and Cross-Disciplinary Perspectives, due to be published this August – details here.

This is an excerpt from chapter 3 (on digitised embodiment) in my forthcoming book Digital Health: Critical and Cross-Disciplinary Perspectives, due to be published this August – details here.

It is not only medical technologies that have contributed to new forms of digitised embodiment. Many popular forums facilitate the uploading of images and other forms of bodily representations to the internet for others to view. Pregnancy, childbirth and infant development represent major topics for self-representation and image sharing on social media. Since the early years of the internet, online forums and discussion boards have provided places for parents (and particularly women) to seek information and advice about pregnancy, childbirth and parenting as well as share their own experiences. Apps can be now be used to track pregnancy stages, symptoms and appointments and document time-lapse selfies featuring the expansion of pregnant women’s ‘baby bumps’. Foetal ultrasound images are routinely posted on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and YouTube by excited expectant parents (Thomas and Lupton, 2015; Lupton and Thomas, 2015; Lupton, 2016).

Some parents continue the documentation of their new baby’s lives by sharing photographs and videos of the moment of their birth (Longhurst, 2009) and milestones (first steps, words uttered and so on) on social media. Wearable devices and monitoring apps allow parents to document their infants’ biometrics, such as their sleeping, feeding, breathing, body temperature and growth patterns (Lupton and Williamson, 2017). The genre of ‘mommy blogs’ also offers opportunities for women to upload images of themselves while pregnant and their babies and young children, as well as providing detailed descriptions of their experiences of pregnancy and motherhood (Morrison, 2011). These media provide a diverse array of forums for portraying and describing details infants’ and young children’s embodiment. A survey of 2,000 British parents’ use of social media for sharing their young children’s images conducted by an internet safety organisation estimated that the average parent would have posted almost 1,000 images to Facebook (and to a much lesser extent, Instagram) by the time their child reached five (Knowthenet 2015). Contemporary children, therefore, now often have an established digital profile before they are even born offering an archive of their physical development and growth across their lifespans.

People with medical conditions are now able to upload descriptions and images of their bodies to social media to share with the world. YouTube offers a platform for such images, but they are also shared on other social media such as Facebook, Instagram, Tumblr and Pinterest. Pinterest offers a multitude of humorous memes and images with inspirational slogans designed to provide support to people with various conditions such as chronic illness. Humorous memes include one with a drawing of a young woman sitting on a bed with her hand over her face and the words ‘Why are there never any good side effects? Just once I’d like to read a medication bottle that says, “May cause extreme sexiness”’. Other images about chronic illness are less positive, used to express people’s despair, pain or frustration in struggling with conditions such as autoimmune diseases, endometriosis and diabetes. Examples include a meme featuring a photo of a person with head bowed down (face obscured) and the words ‘When your chronic illness triggers depression’ and another showing a young woman’s face transposed over an outline of her body with the text: ‘The worst thing you can do to a person with an invisible illness is make them feel like they need to prove how sick they are.’

‘Selfie’ portraits enable people to photograph themselves in various forms of embodiment. There is now a genre of selfies showing subjects experiencing ill-health or medical treatment. These include self-portraits taken by celebrities in hospital receiving treatment for injuries. A larger category of health and medical-related selfies include those that show people in a clinical or hospital setting undergoing treatment, experiencing symptoms or their recovery after surgery. Among the social media platforms available for such representation, Tumblr is favoured as a forum for posting more provocative images that challenge accepted norms of embodiment. One example is Karolyn Gehrig, who uses the #HospitalGlam hashtag when posting selfies featuring her self-identified ‘queer/disabled’ body in hospital settings. Gehrig has a chronic illness requiring regular hospital visits, and uses the selfie genre to draw attention to what it is like to live with this kind of condition. The photographs she posts of herself include portraits in hospital waiting and treatment rooms in glamour-style poses. She engages in this practice as a form of seeking agency and control in settings that many people find alienating, shaming and uncertain (Tembeck, 2016).

People who upload selfies or other images of themselves or status updates about their behaviour on social media are engaging in technologies of the self. They seek to present a certain version of self-identity to the other users of the sites as part of strategies of ethical self-formation (van Dijck, 2013; Sauter, 2014; Tembeck, 2016). In the context of the ‘like economy’ of social media (which refers to the positive responses that users receive from other users on platforms like Facebook, Twitter and Instagram) (Gerlitz and Helmond, 2013), users of these platforms are often highly aware of how they represent themselves. This may involve sharing information about a medical condition or self-tracking fitness or weight-loss data (Stragier et al., 2015) as a way of demonstrating that the person is adhering to the ideal subject position of responsibilised self-care and health promotion.

It can be difficult for users to juggle competing imperatives when sharing information about themselves online. Young women, in particular, are faced with negotiating self-representation practices on social media that conform to accepted practices of fun-loving femininity, attractive sexuality or disciplined self-control over their diet and body weight but do not stray into practices that may open them to disparagement for being ‘slutty’, fat, too drunk or otherwise lacking self-control, too vain or self-obsessed or physically unattractive (Hutton et al., 2016; Ferreday, 2003; Brown and Gregg, 2012). It is important to acknowledge that as part of self-representation, people may also seek to use their social media forums to resist health promotion messages: by showing people enjoying using illicit drugs or alcoholic drinking to excess, for example. Fat activists have also benefited from the networking opportunities offered by blogs and social media to work against fat shaming and promote positive representations of fat bodies (Cooper, 2011; Smith et al., 2013; Dickins et al., 2011).

More controversially, those individuals who engage in proscribed body modification practices, such as self-harm, steroid use for body-building or the extreme restriction of food intake (as in ‘pro-ana’ and ‘thinspiration’ communities) also make use of social media sites to connect with likeminded individuals (Boero and Pascoe, 2012; Center for Innovative Public Health Research, 2014; Fox et al., 2005; Smith et al., 2013). Most social media platforms have polices in place to prohibit these kinds of interactions, but in practice many users manage to evade them. The platforms have a difficult task, because they want to support people’s attempts to communicate with each other about their management of and recovery from health conditions like self-harm or eating disorders but are loath to be viewed as promoting the efforts of those resisting recovery and promoting these behaviours. Their attempts to police the representation of nude human bodies for fear of contributing to pornography are also controversial. Until it changed its policy in 2014, Facebook was the subject of trenchant critique for censoring photographs that women have tried to share on the platform portraying them breastfeeding their infants because of concerns that they were showing their nipples, a body part that Facebook usually prohibits in users’ posts because they are deemed to be obscene. Facebook’s new policy also allowed mastectomy survivors to post images of their post-operative bare torsos, even when nipples were displayed (Chemaly, 2014).

References

Boero N and Pascoe CJ. (2012) Pro-anorexia communities and online interaction: bringing the pro-ana body online. Body & Society 18: 27-57.

Brown R and Gregg M. (2012) The pedagogy of regret: Facebook, binge drinking and young women. Continuum 26: 357-369.

Center for Innovative Public Health Research. (2014) Self-harm websites and teens who visit them. Available at http://innovativepublichealth.org/blog/self-harm-websites-and-teens-who-visit-them/.

Chemaly S. (2014) #FreeTheNipple: Facebook changes breastfeeding mothers photo policy. Huffpost Parents. Available at http://www.huffingtonpost.com/soraya-chemaly/freethenipple-facebook-changes_b_5473467.html.

Cooper C. (2011) Fat lib: how fat activism expands the obesity debate. Debating Obesity. Springer, 164-191.

Dickins M, Thomas SL, King B, et al. (2011) The role of the fatosphere in fat adults’ responses to obesity stigma: a model of empowerment without a focus on weight Loss. Qualitative Health Research 21: 1679-1691.

Ferreday D. (2003) Unspeakable bodies: erasure, embodiment and the pro-ana community. International Journal of Cultural Studies 6: 277-295.

Fox N, Ward K and O’Rourke A. (2005) Pro-anorexia, weight-loss drugs and the internet: an ‘anti-recovery’ explanatory model of anorexia. Sociology of Health & Illness 27: 944-971.

Gerlitz C and Helmond A. (2013) The like economy: social buttons and the data-intensive web. New Media & Society 15: 1348-1365.

Hutton F, Griffin C, Lyons A, et al. (2016) ‘Tragic girls’ and ‘crack whores’: alcohol, femininity and Facebook. Feminism & Psychology 26: 73-93.

Longhurst R. (2009) YouTube: a new space for birth? Feminist Review 93: 46-63.

Lupton D. (2013) The Social Worlds of the Unborn, Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan.

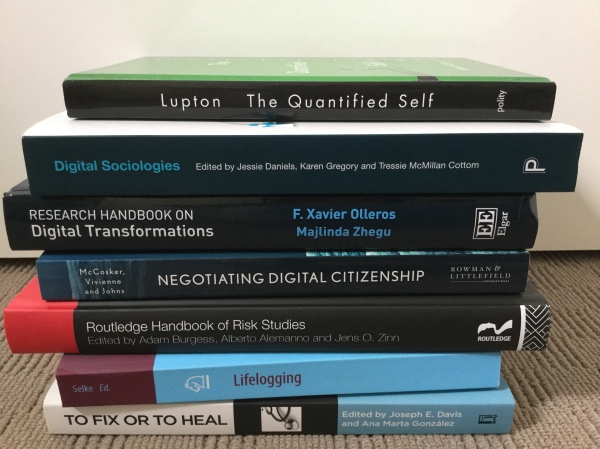

Lupton D. (2016) Mastering your fertility: the digitised reproductive citizen In: McCosker A, Vivienne S and Johns A (eds) Negotiating Digital Citizenship: Control, Contest and Culture. London: Rowman & Littlefield.

Lupton D and Thomas GM. (2015) Playing pregnancy: the ludification and gamification of expectant motherhood in smartphone apps. M/C Journal, 18. Available at http://journal.media-culture.org.au/index.php/mcjournal/article/viewArticle/1012.

Lupton D and Williamson B. (2017) The datafied child: the dataveillance of children and implications for their rights. New Media & Society.

Morrison A. (2011) “Suffused by feeling and affect”: the intimate public of personal mommy blogging. Biography 34: 37-55.

Sauter T. (2014) ‘What’s on your mind?’ Writing on Facebook as a tool for self-formation. New Media & Society 16: 823-839.

Smith N, Wickes R and Underwood M. (2013) Managing a marginalised identity in pro-anorexia and fat acceptance cybercommunities. Journal of Sociology.

Stragier J, Evens T and Mechant P. (2015) Broadcast yourself: an exploratory study of sharing physical activity on social networking sites. Media International Australia 155: 120-129.

Tembeck T. (2016) Selfies of ill health: online autopathographic photography and the dramaturgy of the everyday. Social Media + Society, 2. Available at http://sms.sagepub.com/content/2/1/2056305116641343.abstract.

Thomas GM and Lupton D. (2015) Threats and thrills: pregnancy apps, risk and consumption. Health, Risk & Society 17: 495-509.

van Dijck J. (2013) ‘You have one identity’: performing the self on Facebook and LinkedIn. Media, Culture & Society 35: 199-215.

This is an excerpt from chapter 3 (on digitised embodiment) in my forthcoming book Digital Health: Critical and Cross-Disciplinary Perspectives, due to be published this August – details

This is an excerpt from chapter 3 (on digitised embodiment) in my forthcoming book Digital Health: Critical and Cross-Disciplinary Perspectives, due to be published this August – details